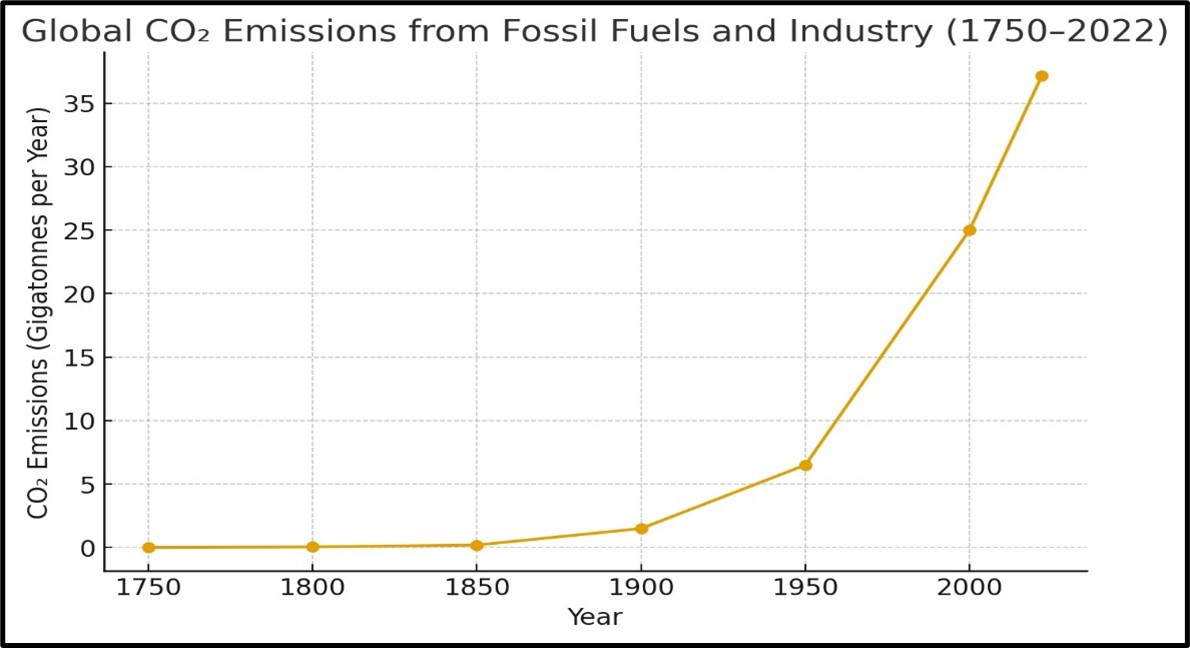

November 05, 2025 (MLN): This first chart tells a simple yet devastating story: as carbon emissions rose, prosperity appeared to bloom. Since the 1960s, every surge in global growth has carried with it a matching rise in CO₂ emissions.

The correlation is no coincidence — it’s the mark of a civilization that built its wealth on fossilized energy.

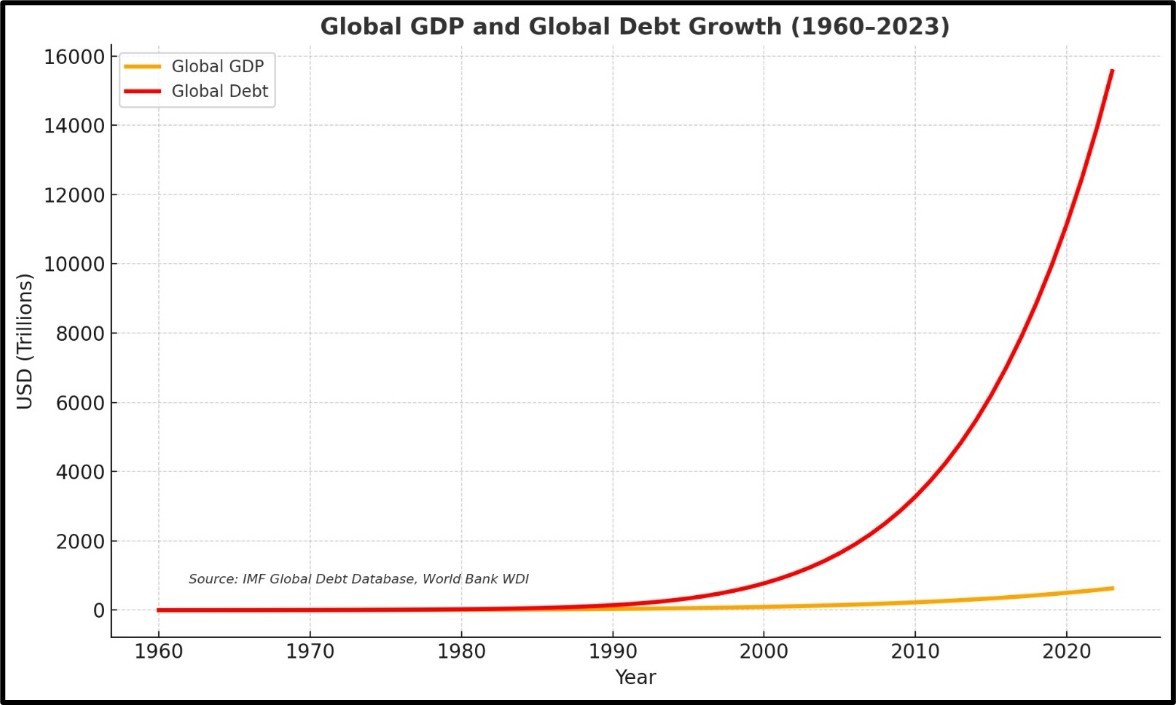

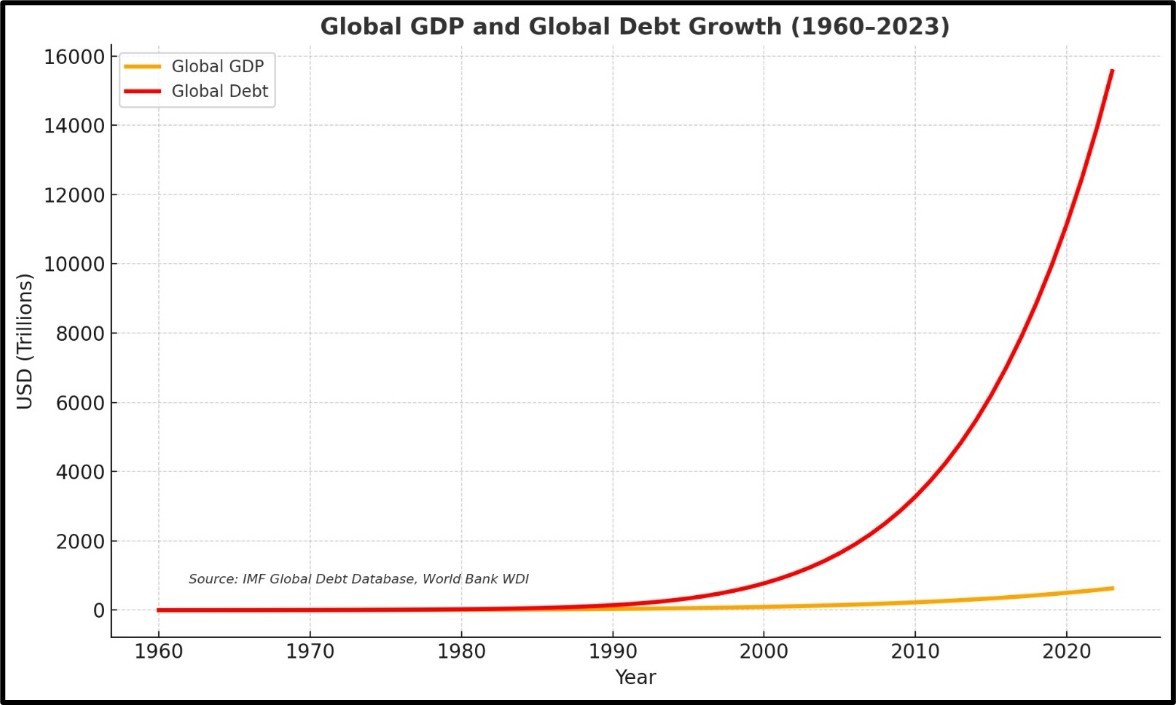

The second chart deepens the picture. Here, global GDP and global debt move together, almost indistinguishably, until around 1990. After that, the curves diverge. Growth slowed, but debt kept rising.

The reason lies in what changed beneath the surface: financial liberalization in the 1980s and 1990s detached credit from real production. Speculation, derivatives, and asset bubbles replaced factories and trade as engines of expansion. The economy became more financialized — growing on paper, not in substance.

Debt no longer funded productivity; it inflated balance sheets. Meanwhile, the carbon curve never paused. Debt had become the accelerant of both consumption and emissions.

History offers perspective and a warning. In 7th-century China, the Tang Dynasty codified detailed lending and land laws, trying to keep money from dominating moral life. The codes limited usury, regulated landholding, and tied economic behavior to Confucian ethics of balance. Yet, even those ancient rulers couldn’t escape debt’s gravitational pull. Borrowing was a tool of survival and often, of conquest.

Centuries later, the pattern repeats. Modern China faces a quiet debt reckoning of its own. Millions of students are burdened with education loans that limit their futures, while the once-mighty real-estate sector, the largest store of Chinese household wealth, is collapsing under mountains of developer debt. What began as an engine of national growth now weighs on an entire generation.

The lesson is timeless: when debt outpaces real value, it traps rather than empowers.

The climate crisis is debt’s newest expression. The world’s carbon debt, the excess CO₂ already in the atmosphere, mirrors global finance. both are products of short-term gain over long-term balance. As nations borrow to grow, they consume more energy, emit more carbon, and borrow again to repair the damage.

Since the Industrial Revolution, human activity has relied heavily on burning coal, oil, and gas, carbon-based fuels that release greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane.

The idea that Earth’s atmosphere could trap heat was first proposed by Joseph Fourier in 1824. Charles David Keeling provided the famous Keeling Curve, showing CO₂ concentrations rising year after year, a steady climb that continues to this day.

Climate finance was meant to reverse that cycle. Yet, the gap remains staggering. According to the Climate Policy Initiative, the world requires around $9 trillion annually by 2030 to align with net-zero goals. Most of this “solution” money will come in the form of new debt, through instruments like green bonds.

Green bonds promise redemption debt rebranded as virtue. But their moral question lingers:

can we solve a debt-fueled crisis with more debt?

Will these trillions go toward transforming energy systems, or merely greening balance sheets?

The world seems ready to borrow again, this time to save the planet it borrowed against.

If debt built our modern world and is now enlisted to rescue it, perhaps the problem lies not in borrowing itself but in what and whom we borrow for. The climate crisis is not just an environmental failure; this crisis is an ethical one.

To fix it, we must first understand its core. A civilization that borrowed too much from its future, financially, ecologically, and morally, eventually found itself bankrupt in spirit, unable to repay the debt of foresight it once ignored.

Disclaimer: The views and analysis in this article are the opinions of the author and are for informational purposes only.

MTB Auction

MTB Auction